ALoneFanCryingInTheWilderness.wordpress.com)

Like any profession, tracing the birth of animation journalism to its exact beginning is a bit of a rough go, but if you want a good place to start you could do worse than to look to the 1970s. It was in 1970, after all, that now noted animation historian Michael Barrier …

… began publishing Funny World, an independent magazine devoted to comic book and animation art …

1976 saw the debut of Remembering Winsor McCay, a documentary dedicated to the life of the great newspaper cartoonist and the father of hand drawn animation. This documentary was the work of Mr. John Canemaker, another influential pioneer into that strange field of study men know as animation journalism.

An entire crop of animation historians, critics, and, most importantly of all, journalists have risen in the wake of men like these to catalogue, chronicle, and document the history of the cartoon art form, and a number of animated television shows, feature films, and short subjects have benefited from the attention such men have paid them. However, a good number of the people who are currently working in this field tend to have a very dim view of a particular type of cartoon that is very near and dear to me; the franchise (or toy as some call them) cartoons of the 1980s.

I've spoken to several people who worked on these types of shows. Some of them are proud of their work. At least one I’ve met seemed to buy into the lie that these shows had no artistic value and were little more than half hour toy commercials.

Whether we’re talking about G.I. Joe, The Transformers, Strawberry Shortcake, the Care Bears, even the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, what have you! Every one of those shows was paid for by toy companies or greeting card companies with the intent of boosting their bottom line.

A major argument from the opposition is that the toy companies dictated which characters from their lines the animation studio could use. There’s also some gobbledygook about the cartoons rotting the minds of children, being preachy, boring, ect. For all these reasons a full decade of animated television has been demonized by a frighteningly large portion of animation journalists and critics.

At first glance a lot of these arguments seem fairly sound, but are they? These cartoons were made to sell toys, therefore they are commercial, therefore they cannot be art. What about product placement in film? Is every movie that flashes a storefront or a logo automatically disqualified from artistic consideration? Both of these types of productions raise funds to help a film or television series raise its budget on the bet that people who see the product will go out and buy it. Isn’t that the same thing?

Bladerunner is considered one of the best science fiction movies of all time and it prominently displays Coke-A-Cola adds?

Does that mean it’s not art? Superman: The Movie was a critically acclaimed, box office hit yet it received $20,000 to work a Cherrios box into one of its scenes.

Now to be fair, product placement is added after the creative process has started, while with toy cartoons the product is the reason there is any production at all. It can be argued that this disqualifies the product placement argument BUT only if you admit that a cartoon’s disqualification from the honor of being able to become ‘art’ depends on whether or not it was created to sell a product. If you do that, it opens a whole new can of worms all together.

Many films are made from successful books. These are preexisting products that have a proven market, in some cases the creator of the preexisting product wields great power over the production even though they might have no film experience at all, and yet think of all the wonderful artistic films that have come from that stock: The Godfather, The Wizard of Oz, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, ect …

“But,” says the opposition, “this is different. These movies were inspired by the books. They were not meant to sell them.”

If that’s the case, then how come whenever a new movie based on a book comes out, Wal-Marts, Krogers, and other stores that may or may not sell that particular kind of book will begin stocking them around the country?

“Oh ho,” says the opposition, “This matters not. For books are creative products created by creative people. They are not the same as mere toys.”

What about the artists, sculptors, and writers employed by toy companies? Are they any different? Keep in mind Hasbro actually paid comic book writers Gerry Conway …

And Dennis O’ Neil …

… to create the back story and many of the names for the Transformers toyline they imported from Japan. Mr. O’Neil who is one of the most respected comic book writers of all time actually named Optimus Prime!

The basic problem with the argument against toy cartoons is that the critics judge the production on the method by which the show was created and not by the finished product. We would hardly expect an art critic called to judge a painting, to turn aside and question the artist about what brushes he used, where he got the money to buy them, and whether or not his inspiration came entirely from his own imagination or from something he saw. No, the critic would examine the finished product and judge it for what it was.

A good movie is not judged because of product placement, or whether or not it’s based on a preexisting idea, or whether or not someone from outside the creative process forced the staff to change an aspect of it, so why should a good cartoon be any different?

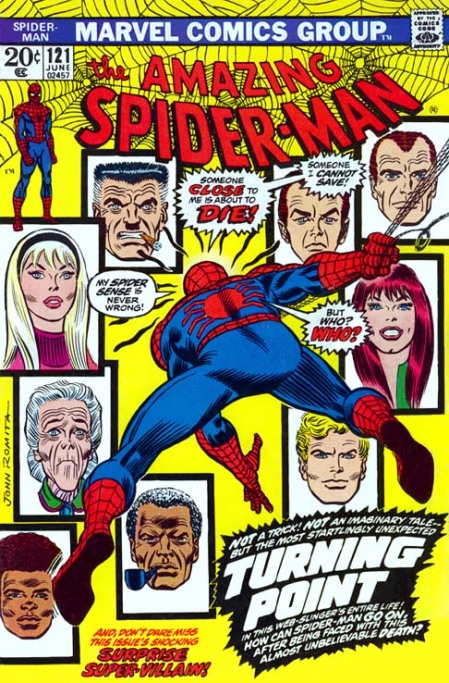

That’s where the next line of attack comes from. We are told that these cartoons are judged badly because they are of an inferior quality. Okay, granted, some of these cartoons did suffer from animation problems. This was the early days of cartoon outsourcing when many shows were animated overseas by inexperienced personnel. You can hardly watch an episode of any show from that time period without witnessing a continuity or design mistake. BUT, the strength of the 1980s wasn’t in the execution of the animation as much as it was in the writing. The 80s saw a sharp increase in action …

… drama …

… characterization

… and suspense!

There are a number of animated features and television shows made both before and after the 1980s that have fantastic art but suffer from story problems; many of these same critics conveniently overlook that.

For instance, one particular animation critic I could name (but won’t because I actually kind of like him) who is also a proponent of toy cartoons = crap, praised Disney’s Tarzan.

Yet the film suffered from underdeveloped characters, an uninspired villain, a disconnected plotline, and a heavy handed moral (kind of funny how those get overlooked when they’re not attached to a toy cartoon) that had already been used in Pocahontas, The Hunchback of Notredame, and actually about 8 out of 10 Disney features from the 90s.

(Pssst: the moral was PEOPLE FEAR AND HATE WHAT THEY DON’T UNDERSTAND. And honestly, it’s good moral, but when you get spoon fed it three or four movies in a row it can get a little tiring.)

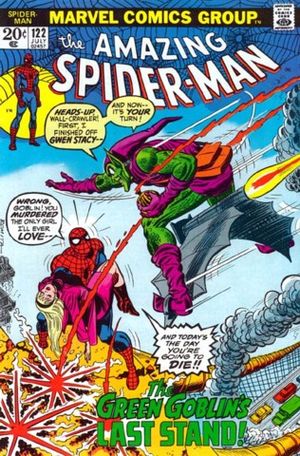

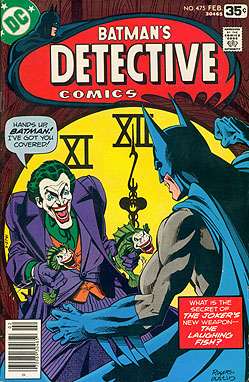

I’ve just never bought into the argument, lackluster stories are okay as long as the film is pleasant to look at. You’ll pardon me for my cynicism but as Doug Walker (an internet critic and comedian) once wrote, “Lame story + Pretty Images = Pretty Lame”. Maybe the cartoons from the 80s do have animation problems, but at the end of the day I’d still rather watch THIS!

… than THIS!

And besides that the few times a project from that time period was able to combine their strong writing and unique designs with well timed animation, it usually turned out something exceptional!

See what I mean.

Now, that’s not to say the writing was always perfect, and while 80s franchise cartoons could be and often were guilty of the same sin of heavy handed morals, they at least put some thought into it. Disney produces animated features for hundreds of millions of dollars and yet it feels like they’re pulling their messages out of their rear ends at times. The Rankin and Bass series Thundercats which was made for significantly less money than any Disney feature I’ve ever heard of, took the initiative to keep a child psychologist on their payroll, so that he could review their scripts and offer suggestions about the commentary of their stories!

That kind of staffing choice gives me a lot more hope for their ability to deliver a positive moral than Disney has, so far.

All of these observations are technical, mind you. Art is not. Art is something that happens, it stays with you and changes the way you think. It makes an impression. The first time I ever saw a cartoon character die was on the Transformers, the images of people degenerating into mutants from G.I. Joe: The Movie horrified me as a child, as did Cobra Commander’s pleas for mercy as his mind and humanity were stripped away from him by the denizens of Cobra-La.

Incidentally, that scene of Cobra Commander got to my older sister so much that for years after, she refused to have anything to do with G.I. Joe.

I can’t speak for everyone else, but what I’m talking about here are a group of cartoons that moved me, scared me, in one or two instances they made me cry: in short, they IMPACTED me as an individual in a way that’s never really lessened. Isn’t that what art is all about? Isn’t that what it’s supposed to do?

“But oh ho,” says the other side, “you’re just being nostalgic.”

Am I? I never saw Thundercats till I was in my 20s. None of the local affiliate stations carried it when I was young. The five part episode that began the second season of that series Thundercats Ho! Still moved me.

In the story Lion-O, the leader of the Thundercats, finds out that there are three more members of his nearly extinct race living on their adopted planet of Third Earth. He and the other Thundercats set out to find them simply because they are their countrymen. This is going to sound corny and sentimental and honestly it is, but in this age of national cynicism, party divisions, and political mudslinging, I found myself stirred by the honest devotion of these flat, two dimensional, “TOYS” as they concerned themselves with the fate of their countrymen simply because they were their countrymen.

This ‘toy commercial’ for which I had no nostalgic value moved me, and impressed its message upon me as an adult. It made me rethink some of my positions concerning people who didn’t belong to my political party, and it made me want to reach out to them more. Maybe I’m an idiot or maybe, just maybe, these shows are better than they are given credit for!

But then prejudice in or against an art form or genre is nothing new. Leonard Da Vinci claimed sculptors were nothing more than common labors and neither their work nor their profession should ever be considered as grand or as lofty as that of the artist and his brush.

There was a time when motion pictures as a whole were not considered art. Dissenters contended that because film was a joint effort by numerous individuals and not the sole vision of a single person, it could never be placed on the same pedestal as novels or paintings or the traditional arts.

This is the same type of self serving, conceited, snobbery that has long afflicted ten years of memorable, well constructed cartoons. But sculpture survived criticism, as film has and it is from film that we can learn a valuable lesson as to how franchise cartoons can throw off the dead weight of these jaded naysayers.

It was the efforts of publications like Cahiers Du Cinema and organized film clubs that began to argue for a film as art.

To break the success of film’s near universal affirmation in the art world down to any one person or source would be futile. It wasn’t a person eventually changed the world’s mind, it was a movement but that movement needed a rallying point before it could gain any steam!

Ladies and Gentlemen and fans of the 80s, we need a voice! If the animation critics we have are not willing to recognize that, then we need new journalists and historians who will and as luck would have it we already have them!

THIS IS CEREAL GEEK!

Founded by British writer/animator James Eatock who has provided content and commentaries for numerous dvd releases of 1980s franchise cartoon in both the U.K. and the U.S., co-producer of Time Life’s phenomenal dvd release of The Real Ghostbusters, the author of The Unofficial Guide to He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, as well as the creator of The He-Man and She-Ra Blog, and a frequent contributor to Master Cast (a He-Man and She-Ra podcast), the distinguished Mr. Eatock is attacking this problem head on!

This type of attention is what is going to raise the bar on our argument with people who want to see these cartoons forgotten and it is an essential tool that can and hopefully will work to change the minds of those who are undecided on these shows and their place in film history.

For those who are curious but not sold on the idea, allow me to present a preview of the magazine that was kindly hosted by toonzone.net

Andrew Cramer who works as a colorist for Cereal Geek has some samples of internal artwork from the magazine on his official website.

You can also find info about it on Cereal Geek’s My Space Page, Face Book Page, Twitter Account or the magazine’s Official Website

Cereal Geek can be purchased courtesy of the magazine’s website or at Graham Cracker Comics.

The magazines tend to run 10-20 U.S. dollars per copy, but if you can’t afford that I suggest you checkout the PDF format downloads for sale on Cereal Geek’s Website. They’re different than the magazines but they still include tons of content as well as some of the published articles that have appeared in previous issues, and the best part is they only run about three buck U.S. currency a’ pop!

And now that I’ve dumped all that awesome in your laps, I’m going to go one further!

How’s that for a smurfin’ good time?

No comments:

Post a Comment